A place where simple art was a courageous act of resistance

"He always believed he could make it just one more day," wrote Lillian Wuttke DeGiacomo in Just One More Day, a posthumous tribute to her husband, William C Wuttke — author of nearly 100 cartoons capturing the brutal realities he and his fellow POWs endured at Mukden Camp, a Japanese prison camp in Shenyang, Liaoning province in Northeast China, during World War II.

Today, reproductions of Wuttke's original works hang on the walls of the Shenyang WWII Allied Prisoners Camp Site Museum, which opened in 2013 — 10 years after former inmates first returned to visit the site in 2003.

Wuttke never made it back — cancer claimed him in 1977. Yet, his work, laced with wit, detail, and piercing insight, endures as a quiet monument to the human spirit: resilience in hardship, dignity in degradation, and artistry under duress.

"His works are as much historical testimony as they are personal expression," says Li Zhuoran, the museum's deputy director. "In the absence of photographs, with the Japanese intent on concealing the truth and many surviving POWs unwilling to relive the pain, much of what happened here might have been lost — were it not for Wuttke and his two fellow covert camp artists."

Li was referring to Barton Franklin Pinson and Malcolm Vaughn Fortier, who also documented camp life through drawings. While Wuttke and Pinson were held in Mukden Camp and forced to work in the drafting office of a nearby Japanese-run labor factory known as MKK, Fortier, an army colonel, was imprisoned in a sub-camp about 200 kilometers to the northwest.

"Wuttke and Pinson had access to drawing tools and materials as draftsmen. But what truly made these caricatures possible was their resolve to defy camp life through creativity," says Li.

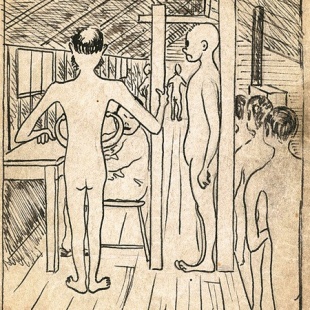

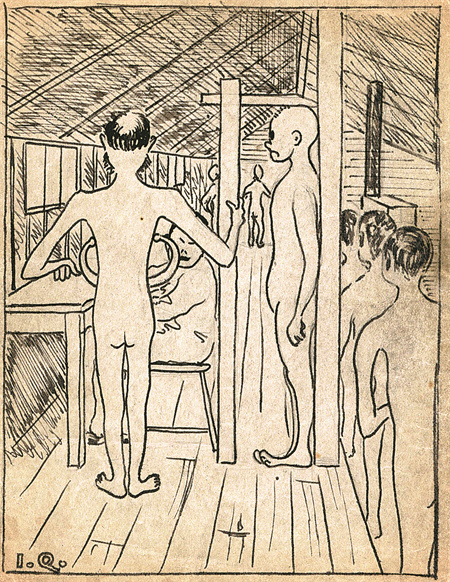

In Just One More Day, cowritten by Wuttke's wife Lillian and son Peter, he is described as smuggling drawings from the factory to his barracks "by plastering them to his body" to evade the guards' daily patdowns — a routine he duly captured in one of his caricatures.

Hunger, cold, and squalid conditions are recurring themes in Wuttke's drawings. One sketch shows POWs "trying to improve their protein intake" by setting a trap for a bird; another depicts them "enjoying a feast of native dog". In a third, a prisoner "acts nonchalant while filching a carrot-like vegetable from the garden".

"If caught, a severe beating would be the least of his worries," Wuttke noted — rarely missing the chance to pair each illustration with a biting caption.

Here, humor was more than an artistic device — it was a means of finding levity in suffering, of preserving sanity by pushing back against the physical and psychological toll of captivity. In one sketch, a POW "warns the rest of the boys that the bedbugs were arriving by parachutes". In reality, lice, fleas, and bedbugs were so rampant in the barracks that they caused countless sleepless nights and had to be pinched to death, often found hiding in the seams of clothing.

Yet, "even the fleas had to stand at kiotsuke (attention) and count off," Wuttke quipped beneath a sketch of fleas standing rigidly in line — a satirical jab at the Japanese guards' brutal practice of forcing POWs to count off in the freezing cold, sometimes for up to an hour.

As for the cold itself, perhaps the most vivid depiction came from Fortier, who drew POWs desperately hacking through ice to restore flow to the camp's frozen water pipes. In another darkly humorous sketch of his, a prisoner enters a latrine on stilts, balancing above an overflowing, frozen mass of diarrhea — labeled "a menace to health".

The harsh conditions fueled the spread of disease both infectious and environmental, top of them dysentery, malaria, pneumonia, typhoid, and beriberi. For the latter, some sufferers even packed their boots with snow or soaked their feet in icy water to ease the pain.

Japanese doctors were brought in, but their motives were highly suspicious — especially given that Mukden Camp was under the control of the Kwantung Army, which not only ruled much of occupied Northeastern China but also oversaw Unit 731, the infamous biological warfare unit of the Imperial Japanese Army.

Included in Wuttke's portfolio is a drawing of POWs — all naked — undergoing various measurements by Japanese doctors "believed to be from Unit 731" as noted by the author.

In her book Guests of the Emperor: The Secret History of Japan's Mukden POW Camp, Linda Goetz Holmes (1933-2020), the first Pacific War historian appointed to advise the US government Interagency Working Group declassifying documents on World War II crimes, asserts that Japanese medical personnel from Unit 731 visited Mukden Camp in early 1943 and conducted human experimentation on Allied prisoners, including Americans.

Wuttke observed that once a POW lost the will to eat, "it was almost over". Recognizing the importance of staying hopeful, one prisoner managed to gather enough scraps of wood and old boxes to build a fullsize bass fiddle — an act captured in one of Wuttke's caricatures. Remarkably, the bass reappears in a group photo taken after the camp's liberation by Soviet troops on Aug 20, 1945, standing as a powerful symbol of the unconquered human spirit.

Equally striking is a black-and-white photograph showing former Japanese guards harvesting potatoes — this time under the watchful eyes of newly liberated Allied POWs. "The role reversal is the ultimate satire, the kind that the camp artists would have truly savored," says Li.

After the war, Fortier published his surviving works in a book dedicated to General Jonathan Wainwright, commander of Allied forces in the Philippines, and "all other POWs, living and dead". To prepare the collection, he painstakingly retraced every line in heavy black pencil — an arduous, monthslong effort that let him relive those harrowing years not merely as a victim, but as a witness compelled to chronicle them, despite having no formal art training.

For his part, Wuttke contributed to acts of sabotage by regularly inserting small errors into technical blueprints. Yet, his most enduring contribution was to memory itself — a memory Robert Rosendahl, one former POW who returned to the site in 2003, admitted having "spent 59 years trying to forget", but ultimately could not ignore.

"Between suffering and survival, some men had found art," says Li.