Nation's innovation surge continues a long tradition

Many in the West mistakenly think that China lacks innovation, but this view is outdated.

China is now showcasing its remarkable capacity for innovation, with its cutting-edge innovations increasingly setting the pace in multiple global industries.

Western narratives about innovation have long been shaped by a narrow historical lens that privileges recent developments in Europe and North America.

This perspective often dismisses the capacity of developing nations to innovate, portraying them as copycats rather than originators. Such a view overlooks the historical reality that China and India were the world's largest economies and centers of innovation until the early 19th century.

From papermaking and gunpowder to advanced agricultural practices and astronomical instruments, China's legacy of innovation is transformative and enduring.

The resurgence of Chinese innovation in the 21st century is not an anomaly but a continuation of a long tradition, now reconfigured through top-down guidance, market competition and global integration.

China's modern innovation trajectory began in earnest with its economic reform and opening-up in the late 1970s. Initially, the country leveraged its comparative advantage in low-cost mass production to stimulate growth. This strategy earned China the proud moniker "factory of the world", producing goods for global markets without developing indigenous brands.

To sustain its industrial base and workforce, China adopted a pragmatic approach: imitating successful foreign designs and brands, in the footsteps of the Japanese industries in the initial stages of its economic recovery after World War II. The approach was not a sign of intellectual deficiency but a calculated move to build industrial capacity and technological expertise in the shortest possible time.

The turning point came in 2001, when China joined the World Trade Organization, facing increased scrutiny over intellectual property practices.

Recognizing the limitations of competing in internal-combustion engine technologies dominated by Western companies, Chinese policymakers pivoted toward electric vehicle, or EV, technology.

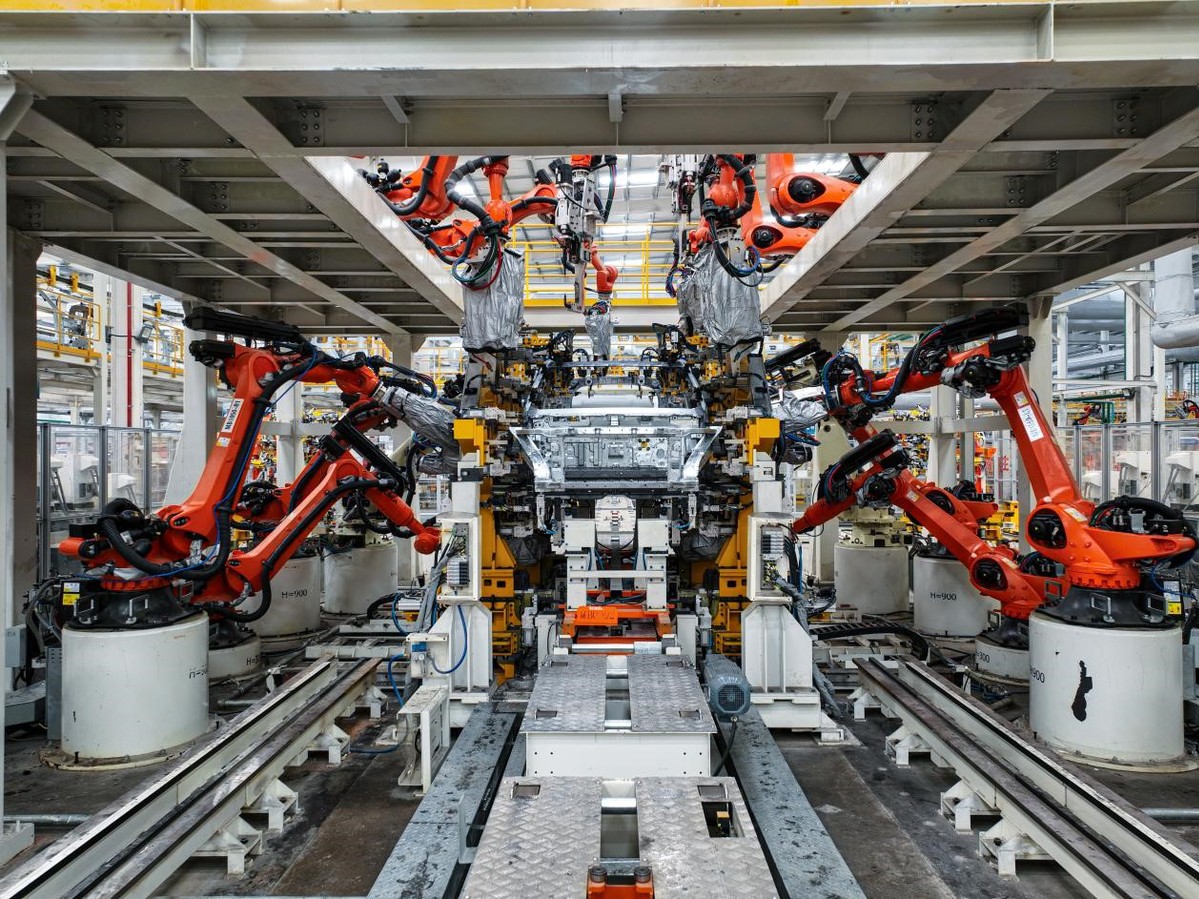

A special EV project was launched in 2001 under the nation's 863 Plan, prioritizing research in pure EVs, hybrid EVs, and fuel cell vehicles. This strategic foresight bore fruit when BYD introduced the F3DM plug-in hybrid in 2008, marking China's entry into the global EV market. The 863 Plan is a top national high-tech development program initiated in March, 1986.

The US-China trade war initiated in 2018 further catalyzed China's innovation drive.

President Xi Jinping's call for "high-level sci-tech self-reliance "spurred massive investments in high-tech manufacturing, artificial intelligence and renewable energy. Xi's vision is not merely defensive but aspirational: to make China a global leader in emerging technologies.

The State's role in this transformation is pivotal. Unlike Western innovation models driven by market forces and individual entrepreneurship, China's approach is State-led, coordinated and systemic. Central to China's innovation strategy is the "innovation chain", a conveyor belt that transforms ideas from State-run laboratories and universities into commercial products.

This model has accelerated progress across multiple sectors.

In the EV industry, companies such as BYD, NIO and Xpeng have introduced groundbreaking innovations, including battery swapping, sideways motion, and even flying.

While critics argue that the Chinese EV market suffers from overcapacity — with 129 brands competing in 2024 and only 15 expected to survive by 2030 — this "survival of the fittest" strategy has quickly winnowed down to a relative few that can not only survive but thrive under fierce competition with their ever-improving technologies.

In AI development, China has made remarkable strides despite US export bans on advanced semiconductors. Domestic tech giants like Alibaba and Huawei have mobilized to develop indigenous AI chips, reducing reliance on foreign suppliers. DeepSeek, a Chinese AI startup, exemplifies this resilience by training models on Huawei chips. This strategic pivot not only ensures continuity in AI development, but also fosters innovation within China's semiconductor industry, laying the groundwork for long-term self-sufficiency.

China's prowess in information technology is equally notable. Companies such as Baidu, Tencent and Alibaba have redefined commerce, financial services and entertainment, often surpassing their Western counterparts in scale and sophistication.

China now leads the world in patent applications, a testament to its innovation capacity. This surge in intellectual property generation reflects not only quantity but also improving quality, as Chinese enterprises expand their global footprint.

In renewable energy, China has emerged as a dominant force. The country's new renewable energy plan emphasizes solar, wind and hydropower, supported by robust infrastructure and policy incentives. China is not merely adopting green technologies, but also shaping their global evolution. According to Harvard's Fairbank Center, China's leadership in clean energy is underpinned by strategic investments, supply chain control and technological innovation.

China's innovation model diverges fundamentally from Western paradigms. In the West, innovation is often driven by free-market forces and individual actors — scientists, engineers, and investors — operating with minimal government intervention.

In contrast, China's top-down model facilitates innovation through strategic planning, targeted funding and robust institutional support. A prominent example is Theseus, a computer-vision sensor company based in Chongqing that originated from informal partnerships between scientific researchers and local government officials. The enterprise was initiated through discussions among members of the Xi'an Institute of Optics and Precision Mechanics, ultimately securing both financial support and infrastructure from district authorities. By 2024, Theseus had become a national leader in its field, collaborating with China Mobile to promote advancements in AMOLED display technology.

The integration of universities, local governments and industry is another hallmark of China's flexible innovation strategy by adopting whatever configuration of partnerships works (the late paramount leader Deng Xiaoping's famous black cat-white cat winning formula comes to mind). Science parks and industrial zones facilitate the commercialization of research and the emergence of new industries. Xiaomi's rapid transition from smartphone manufacturing to EV production within three years exemplifies this agility. Moreover, China's expertise in EVs and drones has enabled it to lead in the nascent field of flying taxis, showcasing the synergies across sectors.

As China consolidates its role as the world's manufacturing hub, its aspiration to become a global innovation leader is a logical progression. Western skepticism about China's innovative capacity reflects outdated assumptions and a failure to grasp the evolving dynamics of global technology. China's State-led model, while distinct from Western norms, is producing tangible results across multiple domains. From EVs and AI to renewable energy and information technology, China is not merely catching up — it is setting the innovation pace.

The author is a distinguished research professor at the University of California, Los Angeles.

The views do not necessarily reflect those of China Daily.