Forbidden gates swing open

An exhibition at the Palace Museum honors treasures and the generations who have preserved them through war and restoration, Wang Kaihao reports.

Meridian Gate towers above the entrance to the Palace Museum in Beijing, once China's imperial palace from 1420 to 1911 and also known as the Forbidden City. During the imperial years, numerous royals, high officials and nobles walked through this gate, which stands for solemnity, ritual and order. They stepped into a "forbidden" place, closed to outsiders where the course of their own destinies — and often the fate of the country — was shaped.

In October 1925, a new chapter opened when the Palace Museum was established, unlocking the gates for the public and marking the beginning of a story about custodians devoted to safeguarding and extending an unbroken civilization.

A century later, tourists ascend the Meridian Gate Galleries, a privilege that was unimaginable even for most high officials who passed the doorway in ancient times. Here, a special exhibition A Century of Stewardship: From the Forbidden City to the Palace Museum lifted its curtain on Monday and will run until year's end.

More than 200 carefully chosen exhibits, including paintings, calligraphic works, jade, bronze ware, gold ware, porcelain and architectural components, among others, are on view for the centennial. The exhibition allows people to see not only the panorama of the Forbidden City from above, but also the cultural lineage borne within its walls through centuries of Chinese history.

Its foreword declares: "You will witness how generations devoted themselves to the nation and its cultural legacy — how they explored the civilization of rituals and rites within palace walls and discovered continuity in ancient collections; how they revived forgotten histories through scholarship and awakened silent artifacts to resonant life."

Truly, a hasty half-day tour of its three galleries feels like time travel through millennia. "Cultural relics are the best records of civilization," Xu Wanling, the exhibition's curator, tells China Daily.

"Through relics, we want visitors to see those historic moments and the people behind them."

Great miracles

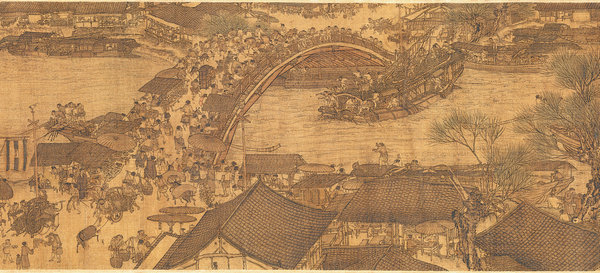

One monumental treasure on view, and perhaps the most famous painting in Chinese history, Along the River During the Qingming Festival, was unrolled for the first time in a decade.

Created by Zhang Zeduan from the imperial painting academy of the Northern Song Dynasty (960-1127), this silk scroll, which measures over 5 meters, depicts the flourishing landscape of the national capital of Dongjing (present-day Kaifeng, Henan province) through vivid portrayals of hundreds of figures, over 100 houses, 25 boats and countless details of urban life.

Seals of nearly 100 collectors, impressed over centuries, testify to the painting's journey through history.

The scroll was lost during the war that ended the Northern Song Dynasty, stolen from the palace, passed from one literati's hand to another and from some powerful minister's residence to the next, before eventually entering the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) royal collection in the late 18th century.

Yet, turmoil returned. The last emperor Puyi, who continued to live in the Forbidden City in the 1920s after the fall of the monarchy, managed to get the painting out of the palace again. He later took it, along with many other relics, to Northeast China where he presided over a puppet regime under Japanese occupation. Many assumed the painting was lost forever during the chaotic end of his rule.

Against all odds, it resurfaced in 1950. Cultural relic researchers found it in a wooden case abandoned by Puyi when his puppet state collapsed. The painting later returned to the Forbidden City, intact, like a miracle.

From 1960, Feng Zhonglian, a painting expert, spent 20 years painstakingly copying the scroll, working despite her frail health and social upheaval, creating a modern echo of Zhang's masterpiece.

Her duplicate is displayed alongside the original at the exhibition, adding an extra chapter to its odyssey.

Xu Tong, a researcher from the painting and calligraphy department of the Palace Museum, is in charge of selecting about 30 key works for this exhibition.

"Many relics did not always stay in the palace peacefully," she says. "The hardships they endured just tell the exceptional history of this museum."

In the 1930s, as Beijing faced imminent war, Palace Museum employees transported more than 13,000 crates of relics first south, then west. After the war, they retraced their path to return them. Not a single piece was lost during this decades-long trek.

"We cannot explain these miracles. It can only be credited to the blessing on our nation," Ma Heng, then director of the Palace Museum, wrote in 1947. Now, as some of those once-journeying relics reappear in the centennial exhibition, their presence testifies again to the custodians' determination.

Devoted protectors

Another highlight, the Tang Dynasty (618-907) painting Five Oxen, embodies a modern tale of perseverance. One of the earliest surviving Chinese paintings drawn on paper, this scroll in the Qing royal collection disappeared after the Eight-Nation Alliance invaded Beijing in 1900.

It surfaced again in the 1950s at a Hong Kong auction. Premier Zhou Enlai then directed efforts to negotiate and buy the painting and some other relics, racing against the clock and making the mission a matter of national urgency.

Xu Bojiao, a banker from a family of cultural relic appraisers, was entrusted with the task.

In a letter written to Zheng Zhenduo, then the country's cultural heritage administration chief, he said: "One more relic we acquire, one more thing we've done for our nation." This letter is itself displayed in the exhibition.

"We're not qualified to judge history," Xu Wanling says. "But people from history have spoken for us.

"In the early 20th century, when the country endeavored to overcome years of weakness, some cultural relics were lost," she adds. "Thanks to our predecessors' efforts, the treasures came back. It's also a reflection of the times."

Over 280,000 cultural relics entered the inventory of the Palace Museum after the founding of the People's Republic of China in 1949.

Xu Tong highlights that Five Oxen also shows state-of-the-art techniques of restoration. When it was unfurled in front of veteran restorer Sun Chengzhi in 1977, it had more than 300 holes and badly faded colors, posing a huge challenge. Through meticulous handwork, Sun fixed it, giving the splendor and honor back to this time-tested treasure.

A similar marvel happened to another Tang exhibit, a guqin (an ancient Chinese plucked seven-string musical instrument) with the resounding name Dasheng Yiyin, or "lingering sound of the great sage".

When it was first found a century ago in the Qing royal inventory, it was registered merely as "a broken guqin" because of its poor condition. Its value was only recognized more than 20 years later. After restoration in 1949, it regained recognition as a celebrated Tang-era masterpiece.

Continuity of lineage

In the eastern gallery of Meridian Gate stands a bronze square jar with lotus and crane decoration, or Lianhe Fanghu, at the center, dating back to the Spring and Autumn Period (770-476 BC), or the age of Confucius. It reflects a time when rituals shifted and old hierarchies faltered. Unearthed in 1923 from a tomb in Henan province, it was allocated to the warehouse of the Palace Museum in 1950.

A cast figure of a crane perches on top of the jar with its wings fully spread and its beak slightly open as if about to call. It is surrounded by two layers of flourishing lotus petals. The body is decorated with sacred animals in various shapes.

Late historian Guo Moruo commented: "This artifact made a breakthrough from previous bronze wares, which had been of a solemn atmosphere. Its freshness and vitality also stood for a transforming society."

To the south lies the Gold Cup of Eternal Territorial Integrity, created during the Qianlong era (1736-95).The vessel reflects the wealth and social stability of the peak time of the Qing Dynasty, whose Emperor Qianlong was an ardent connoisseur of art.

"The pair may reflect different historical backgrounds, but they may share a common wish for prosperity and auspiciousness," Xu Wanling explains. "They suit this anniversary, which celebrates heritage and looks to the future."

To the north of the bronze jar, a jade disc known as bi, from about 2,200 years ago, tells another story of blessings and rituals. Through the hole in its center, visitors can have a glimpse of the crane figure as well.

Also from the former Qing royal collection, the jade disc, with a 40-centimeter diameter, is one of the largest heirlooms of its kind in Chinese history.

"By aligning the three pieces along the gallery's axis, we highlight cultural continuity," the exhibition curator says. "The royal collection of the Qing Dynasty is part of this lasting legacy of our civilization."

Yi Peiji, one of the cofounders of the Palace Museum, once said: "The Forbidden City is the repository of thousands of years of Chinese cultural treasures. Since it became a museum, the treasures, which were confined to secret halls for a few, are now shared with the people."

Today, digitized editions of many highlights appear on screens with naked-eye 3D effects. Yet, while technology impresses, modern visitors may take such wonders for granted. But for those visitors stepping into the Forbidden City for the first time 100 years ago, the visual impact of these long-hidden cultural relics would probably have been overwhelming.

"It's hard to imagine their excitement," Xu Wanling says. "But seeing the same objects, we can still feel a resonance with them."

A porcelain bowl in painted enamel, decorated with mandarin ducks and a lotus pond, was among the relics displayed in the earliest days of the Palace Museum.

Now quietly resting in the gallery, with an old photograph placed behind it, the Qianlong-era bowl retains its vivid colors, unfaded despite the passage of time.

Time seems irrelevant. A century on, visitors may still share a moment of wonder with those early audiences: This saga of civilization endures.

Contact the writer at wangkaihao@chinadaily.com.cn