When snail soup becomes a cultural power move

There's something delightfully absurd about the fact that one of China's most talked-about culinary exports today smells like gym socks but tastes like heaven. Enter luosifen, a rice noodle dish made with a pungent snail broth. Once a humble street food in Liuzhou, luosifen is now a social media sensation and global supermarket fixture.

What began as a simple dish made with simple ingredients for factory workers has set an example of how regional foods can reflect broader trends in industrial development, cultural confidence, and evolving manufacturing capabilities.

The origin of luosifen is both incredible and instructive. In the 1970s, workers in Liuzhou, Guangxi Zhuang autonomous region, combined leftover pickled bamboo shoots, tofu skin and river snail soup to make a sour-spicy bowl of soup that quickly caught the fancy of street food enthusiasts. Its contrasting elements became its brand: the smell repels, the flavor converts.

The viral luosifen craze on TikTok has deep roots in the region's history — with 26,000-year-old snail shell mounds unearthed nearby showing early humans were already eating river snails.

But the dish's cultural importance goes far beyond its recent popularity. It is deeply rooted in a local food ecosystem shaped by the region's multi-ethnic heritage. The rice noodle base reflects the meeting point of northern Han Chinese flour tradition and the rice-farming culture of the Zhuang people, while their love for sour foods — fermented bamboo shoots, pickled beans, and sour meat and fish — draws from the culinary legacies of the Yao, Miao and Dong ethnic minority groups.

In 2018, the importance of luosifen was recognized by a national geographical indication. In 2021, it was formally listed as a national intangible cultural heritage. The dish, once a grassroots food, has become a symbol of traditional culinary art and cultural continuity.

Yet luosifen's rise is about more than adventurous eating. It reflects a deeper shift: how China's regional cultures, long overshadowed in global markets, are now going mainstream — with help from high-tech manufacturing and digitally savvy branding.

The technical innovation behind luosifen's global success is often overlooked. At first, the dish's bold flavor was too volatile for long-distance shipping. That changed when China's food tech sector developed sterilization and vacuum-packaging techniques that stretched luosifen's life from 30 to 180 days. What once could be eaten only fresh at roadside stalls is now produced on standardized, industrial scale — and shipped globally. From 2015 to 2024, the luosifen supply chain grew from a niche 500 million yuan ($69.91 million) operation to a 75-billion-yuan juggernaut, with more than 100 million packages shipped per year.

Equally important is the logistical transformation. The New International Land-Sea Trade Corridor, which connects western China to 555 ports worldwide, reduced shipping time by up to 20 days. Using rail-sea intermodal transport, packaged luosifen now travels from Liuzhou to the Beibu Gulf and on to Southeast Asia, Europe and North America, bypassing the seasonal constraints of traditional river-ocean routes and slashing costs in the process. This improvement in inland connectivity marks a subtle but significant development in China's international trade logistics, with the rise of luosifen setting an example of how local products can enter global circulation.

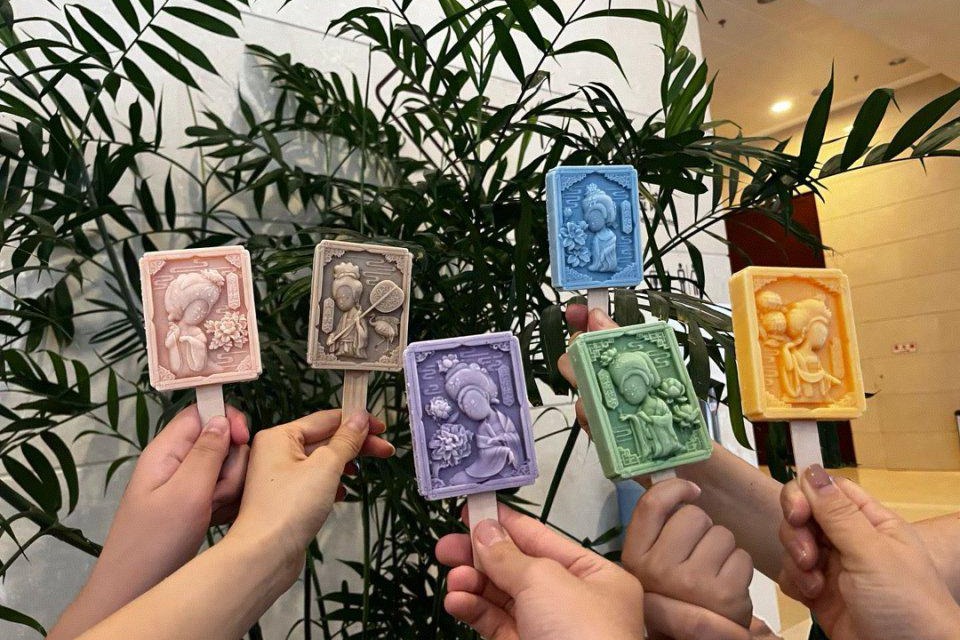

But what makes luosifen a phenomenon isn't just efficiency; it's also storytelling. Social media turned this odorous noodle soup into a sensation thanks to the cinematic storytelling of influencers like Li Ziqi. In her videos, luosifen isn't just food but an ode to Chinese pastoral life, which has turned a steaming bowl of noodle soup into a cultural icon.

Luosifen's global popularity is not a fluke, but an example of cultural confidence. It represents a form of aesthetic diplomacy, where smell and flavor translate what numbers cannot. When a bowl of noodles soup becomes a cross-border craving, it signals something deeper: a world increasingly open to cultural specificity over generic global sameness.

This is what sets today's Chinese brands apart. They're not just selling goods, but also sharing aspects of cultural aesthetics, identity, and narrative. In New York, "Oriental Leaf" tea is touted as a clean-living tonic; in London, HeyTea has built a tea house near the British Museum, marrying modern design with Chinese ink wash aesthetics. In student apartments and dormitories across Europe, Lao Gan Ma chili sauce is an essential pantry item, drizzled over spaghetti or ramen noodles.

More than showing changing tastes, such developments portray China's transition from the "world's factory" to a global tastemaker. The age of low-cost, no-brand exports is fading, being gradually replaced by high-value, culturally-infused products that blend functionality with interesting tales.

China's manufacturing is no longer just about scale; it's also about synergy. When food processing, logistics innovation, digital marketing, and heritage protection intersect, the result is a product that transcends borders. Luosifen offers a case study in how cultural appeal can build gradually and gain wide recognition over time.

Luosifen's improbable journey, from a factory town snack to global comfort food, captures this shift. It's a dish that is too smelly to love, too delicious to ignore. It's winning hearts not because it was designed for export, but because it is unapologetically Chinese.

In a world awash with homogenized products and flat global brands, this kind of cultural specificity is starting to matter again. And for China, that may prove to be its greatest competitive advantage, not only in trade, but also in taste, and in how the world sees it.

The author is an associate researcher at the Institute of Finance and Banking of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences and a senior research fellow at the National Institution for Finance and Development. The views don't necessarily reflect those of China Daily.

If you have a specific expertise, or would like to share your thought about our stories, then send us your writings at opinion@chinadaily.com.cn, and comment@chinadaily.com.cn.